Will your next car be hydrogen powered?

Hydrogen is kind of a big deal these days. Well, truth be told, it’s always been a big deal; the most common element in existence, this natural gas has long cemented its status as the building block of the universe.

But engineers, scientists, and other VCPs (very clever people) are just beginning to tap into the potential of hydrogen as an energy source on our planet.

Hydrogen atoms provide an abundant and clean form of energy, but they rarely exist in isolation. Overwhelmingly, hydrogen exists in the natural world as a compound atom (i.e. attached to other types of atoms). This means that for hydrogen to be produced at an industrial scale, hydrogen atoms must be separated from the other atoms it is attached to in order to be used as a fuel.

Several vehicle manufacturers have begun to produce hydrogen fuel cells for transport in the past few years, although the technology is not currently as popular globally as alternatives such as hybrids or battery-powered electric vehicles (EVs).

While there are several small companies around the world producing cars capable of running on hydrogen (the UK-based company Riversimple, for example) there are only three major manufacturers that have committed to the technology so far: Hyundai, Honda, and Toyota.

Several hydrogen-powered racing cars and hypercars also exist in various stages of development, such as the Hyperion XP-1, which is set for release in 2022.

Hydrogen cars in Australia

Infrastructure for refuelling of commercial hydrogen cars is somewhat lacking in Australia, though there have been several inroads in 2021.

Hydrogen fuel must be stored as a liquid at temperatures between negative 20 degrees Celsius and negative 40 degrees Celsius. Filling up a car takes about three to five minutes in total, a roughly comparable speed to traditional combustion engine vehicles and considerably quicker than EVs.

The first public hydrogen charging station in Australia was launched in the Canberra suburb of Fyshwick earlier this year, which serves as the official refuelling station for the Federal Government’s fleet of 20 hydrogen-powered Hyundai Nexo SUVs.

This was followed by a second station in the western suburb of Altona, Melbourne, a few weeks later, with a third station planned for Brisbane in the next few months.

So how does this compare to the global average? Well, by the end of 2019, there were 432 hydrogen filling stations worldwide, with 330 of those being open to the public. Europe had 177, with the majority in Germany and France, and Asia had 178, with the majority in Japan and South Korea.

In the United States, there were 74 filling stations, with more than half located in the state of California, where hydrogen car owners benefit from considerable state government incentives.

A hydrogen filling station in Hamburg, Germany (Image: Shutterstock)

How they work

Hydrogen cars look pretty similar to other types of cars from the outside, but their workings are clearly quite different. So how do their engines work?

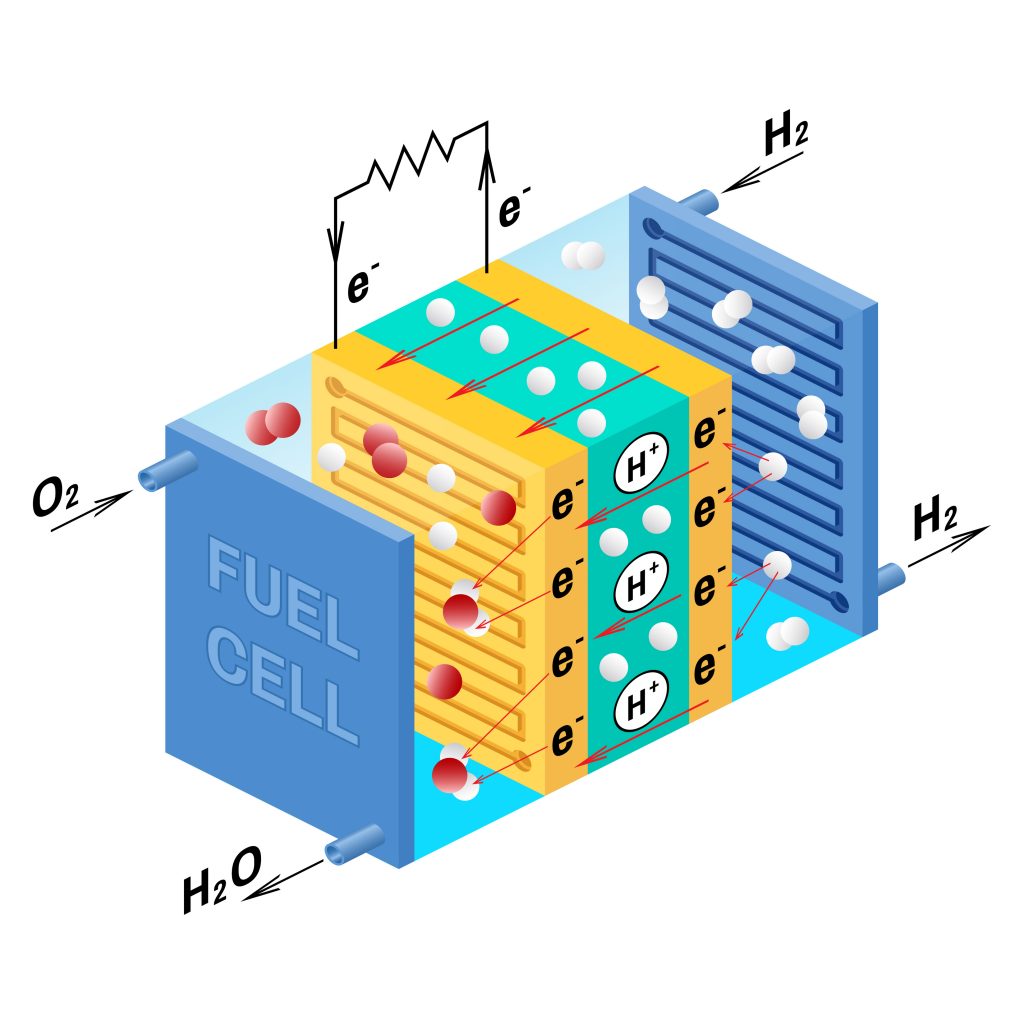

Hydrogen-powered cars use a combination of a fuel cell, hydrogen tanks, and an electric motor to provide the energy to move the car.

In simplified terms, air passes into the car’s fuel cell (usually through the grille) in combination with hydrogen from its tanks. The hydrogen then reacts with the oxygen from the air to produce electricity and water.

The electricity then passes to the vehicle’s motor and water vapour and heat pass out of the exhaust.

A diagram showing how a hydrogen fuel cell works.

Other vehicles?

Hydrogen isn’t just useful for cars — all kinds of vehicles, including larger transport such as trucks, ships, and trains and trams (collectively referred to as ‘hydrail’) can benefit from the technology, not to mention wider energy infrastructure.

Scott Nargar, Senior Manager of Future Mobility & Government Relations at Hyundai Australia, explains that fuel cells can be stacked to power larger vehicles such as its Xcient truck series.

“In a truck we’d stick two or three of those fuel cells together; it’s almost like stacking Lego blocks,” he explains. “The more power and torque you need, the more of those fuel cells you put together. Of course, you have a bigger motor or a bigger differential on a heavy vehicle.”

Like hydrogen cars, hydrogen trucks also take considerably less time to refuel than their EV equivalents, and their batteries are considerably lighter, which could allow for heavier haulage weights to improve transport efficiency once the technology starts to come into its own.

Overall, hydrogen vehicles are still in their early days, but it goes to show there’s a lot of potential in even the smallest of atoms.

Explorewith Natural Gas Subscribe